A body on which violence has often been unleashed, a body humiliated, mocked, beaten, ghettoized, violated. This is the woman’s body, a body made of flesh and bone that has often been put in the centre of attention just to be looked at, observed, desired.

Eyes, mouth, hair, breasts, hips: in the public opinion, in culture, in language, it seems very often in that being a woman focuses everything there and this seems a sad paradox if you think of how many battles, how many speeches, how many protests have been made by women all over the world to say loudly that the body is theirs. Rape is the perverse and animal synthesis of all violence – the daily one, of science, of gaze, of words and gestures, as Franca Ongaro Basaglia says in “A trial for rape”.

Eyes, mouth, hair, breasts, hips: in the public opinion, in culture, in language, it seems very often in that being a woman focuses everything there and this seems a sad paradox if you think of how many battles, how many speeches, how many protests have been made by women all over the world to say loudly that the body is theirs. Rape is the perverse and animal synthesis of all violence – the daily one, of science, of gaze, of words and gestures, as Franca Ongaro Basaglia says in “A trial for rape”.

Rape is among the most morally controversial issues of cinema, for its representation, for how the public is accustomed to seeing and for how the viewer is forced to understand those images through the norms of society. How does the cinema tell violence about women? From the etymological point of view stuprum is disgrace, disgrace, shame. Disgrace to whom? For society (rape was considered a crime against morality until 1996 in Italy) and it’s been like that for a long time, until suddenly the direction changed.

Everything moves from the offender to the one who suffers it despite the fact that most of the time the woman still feels deeply, unjustly and painfully guilty

in many films you see clearly how the woman finds it difficult to talk about what happened to her, to denounce him knowing that she will be judged for the way she was dressed when she suffered violence or for the life she leads.

Cinematographe.it, the Beauty and the Beasts

The film “The Beauty and the dogs” by the Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania shows Mariam’s odyssey, who has suffered violence from three policemen. The young woman, violated in body and soul, lives a journey in the senseless and inhuman bureaucracy, during which she suffers blackmail and other violence. The body is the home of a person, the place where you must feel safe, it is no coincidence that often the rape takes place after the rapist has penetrated inside the house of the victim.

The film “The Beauty and the dogs” by the Tunisian director Kaouther Ben Hania shows Mariam’s odyssey, who has suffered violence from three policemen. The young woman, violated in body and soul, lives a journey in the senseless and inhuman bureaucracy, during which she suffers blackmail and other violence. The body is the home of a person, the place where you must feel safe, it is no coincidence that often the rape takes place after the rapist has penetrated inside the house of the victim.

It is a parallelism between home and body: the woman is penetrated into her home as the executioner enters the place where she should feel protected. An example of this is the famous “Clockwork Orange” (Stanley Kubrick) and also “Elle” (Paul Verhoeven) in which a wonderful Isabelle Huppert becomes the victim of sexual violence right within the home.

Rape: the expression of a man who by “contract” wants to prevaricate

Women were muted for a long time mute – it is a testimony of it, metaphorically, the protagonist of MS 45. “The angel of revenge” of Abel Ferrara who is unable to speak for a trauma suffered to the vocal cords. She often tried to explode in disarticulated screams, continued to fight strenuously to give shape to his silence and then fill it with words, sincere, real, important, honest words. At that point the woman begins to rebuild herself, to say, do, think, vote, the male for his part gradually loses the centre and cannot accept to be dethroned and ridiculed: because of the cultural constructions, the man has to be masculine, powerful, always ready, while the woman must be submitted to him.

Women were muted for a long time mute – it is a testimony of it, metaphorically, the protagonist of MS 45. “The angel of revenge” of Abel Ferrara who is unable to speak for a trauma suffered to the vocal cords. She often tried to explode in disarticulated screams, continued to fight strenuously to give shape to his silence and then fill it with words, sincere, real, important, honest words. At that point the woman begins to rebuild herself, to say, do, think, vote, the male for his part gradually loses the centre and cannot accept to be dethroned and ridiculed: because of the cultural constructions, the man has to be masculine, powerful, always ready, while the woman must be submitted to him.

If she managed to have a different and better role in society, if she’s freer, then the male must have some benefit from it. When a man sees and wants a woman, he must have her, in order to possess her both physically and psychologically, he can’t accept a no as an answer, because this is what society wanted for a very long time.

In the movie “Hitch – Hike” by Pasquale Festa Campanile, the main character is Eve (Corinne Cléry) and she’s been called, in front of her husband Walter Mancini (Franco Nero), “beautiful cunt” by Adam, a hitchhiker that later will reveal himself as a crazy violent murderer and raper. Eve, for the both of them, is not a woman, a human being, but she’s considered as a sexual organ. She’s in the viewfinder of the male’s gaze (the film opens with the husband who aims with the gun the wife), she’s a sex to want, to possess, to penetrate, even against her will.

In the movie “Hitch – Hike” by Pasquale Festa Campanile, the main character is Eve (Corinne Cléry) and she’s been called, in front of her husband Walter Mancini (Franco Nero), “beautiful cunt” by Adam, a hitchhiker that later will reveal himself as a crazy violent murderer and raper. Eve, for the both of them, is not a woman, a human being, but she’s considered as a sexual organ. She’s in the viewfinder of the male’s gaze (the film opens with the husband who aims with the gun the wife), she’s a sex to want, to possess, to penetrate, even against her will.

In fact, the husband often, while being drunk and with little desire of working, possess the wife, whom accepts because it’s how things are supposed to go

Adam enters forcefully in the journey of the couple and this language in which a part (the female sexual organ) becomes the whole (the woman) will be a constant until you get to the sexual violence perpetrated because the woman wants it and for this she lives. She, says Adam, is like a spring, you just need to know how to operate. The rape becomes the way Adam wounds to death the other man who assists powerless not only to the act but also to the destruction of his manhood: the body of Eve, immobilized by fear, at first undergoes violence, then gives in and starts to feel pleasure, as was often thought at the time.

From “Last tango in Paris” to Lola Darling: the rape of Bernardo Bertolucci and Spike Lee

How can we forget the famous scene of “Last tango in Paris” by Bernardo Bertolucci, where Paul sodomises his love Jeanne. They meet by chance; they desire each other and then they desperately mate in an apartment without ever saying their names to each other. The scene of rape with the butter makes sense if we discover from the newspapers that Bernardo Bertolucci and Marlon Brando had agreed to not tell to the actress about it, to make everything more “credible” and “realistic”; the humiliated and frightened face of Schneider has an important, fundamental value because

How can we forget the famous scene of “Last tango in Paris” by Bernardo Bertolucci, where Paul sodomises his love Jeanne. They meet by chance; they desire each other and then they desperately mate in an apartment without ever saying their names to each other. The scene of rape with the butter makes sense if we discover from the newspapers that Bernardo Bertolucci and Marlon Brando had agreed to not tell to the actress about it, to make everything more “credible” and “realistic”; the humiliated and frightened face of Schneider has an important, fundamental value because

in that face there is the feeling of other women who have experienced the same humiliations and have had the same violence

In “Once Upon a Time in America” by Sergio Leone, the desire takes Noodles who brutally rapes Deborah in the car because he understands that she will never be his. They’ve always been friends with a pure and delicate friendship, but he also has always been in love with her. So, it’s a scene that rips out the heart and shows how disturbing, distorting male vision is. It is precisely these two elements, on the one hand a man perpetually desirous, on the other a woman who as such “provokes” the other, set in motion the tragedy of a body, a woman, a society that unfortunately never ceases to claim victims.

In “Once Upon a Time in America” by Sergio Leone, the desire takes Noodles who brutally rapes Deborah in the car because he understands that she will never be his. They’ve always been friends with a pure and delicate friendship, but he also has always been in love with her. So, it’s a scene that rips out the heart and shows how disturbing, distorting male vision is. It is precisely these two elements, on the one hand a man perpetually desirous, on the other a woman who as such “provokes” the other, set in motion the tragedy of a body, a woman, a society that unfortunately never ceases to claim victims.

“Whose cunt is this?” Jamie asks Nola in the film “Lola Darling” by Spike Lee. It’s in this sentence the story of the protagonist between felt desire and provoked desire. Nola is a “free” woman, she is a desirous subject, or so at least she thinks, because she gradually understands that hers is not an autonomous act but an attempt to reward the male.

In the rape scene, by what appears to be the mildest man among her lovers, Nola is terrified

she is punished as free, treated like a prostitute because for Jamie someone who acts like her – a sexually active woman – can be treated only in this way. Faced with the debasement, humiliation, pain not only physical but also emotional, she does not resist, but she loses the property on her body and to the question asked by Jamie she answers: “Yours”, taking a thousand of steps back.

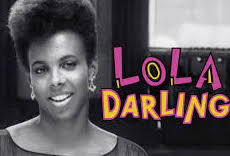

Rape and Revenge: the centre of a subgenre that shows change

A woman is kidnapped, beaten, raped, by men who have the right to rape her, because she is their property, not of herself; it is right here the strands of one of the kinds that gives the most inspiration on this: “The Rape and Revenge” (which perfectly represents the social changes regarding the woman, first caged in a stereotypical prison then finally freed) in which in the first part of the film there is

the sexual violence suffered and, in some cases, the killing of the protagonist, and in the second the revenge by the victim

who looks like a vigilante (the highlight of this is Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge), or by her family. In “The Last House on the Left” (1972), the first work by Wes Craven, founder of this genre, he shows two women, Mari and Phyllis, kidnapped, beaten, raped, killed by Krug and his gang – in which there is also a woman, Sadie. If the woman is ontologically “pure pussy”, the male, only partially identified in his genitality, is above all action, thoughts, politics. So, while the sexual violence is carried out the pawns are repositioned: man=active, woman=passive.

who looks like a vigilante (the highlight of this is Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge), or by her family. In “The Last House on the Left” (1972), the first work by Wes Craven, founder of this genre, he shows two women, Mari and Phyllis, kidnapped, beaten, raped, killed by Krug and his gang – in which there is also a woman, Sadie. If the woman is ontologically “pure pussy”, the male, only partially identified in his genitality, is above all action, thoughts, politics. So, while the sexual violence is carried out the pawns are repositioned: man=active, woman=passive.

Mari represents, along with Phyllis, what in these years some men are afraid of: she proudly shows her naive and young sexuality, her independence, her autonomy and for this reason she is dramatically and brutally punished. “Ugly bitch, now I’ll fix you”. That’s what the rapists say to the victim, because for the rapist

the sexual act is a punishment, a way to regain their power

Useful are the words of Susan Brownmiller who in 1975 in a text defines rape: “a conscious process of intimidation with which all men keep all women in a state of fear”. In other words, according to Brownmiller, rapists do not rape because they want to have sex, they rape because they want to exert a psychological (and also physical) power on the woman, in fact in the Craven movie there is no desire in it. The eye of the spectator makes it difficult to look, to keep his gaze, to accept the image: there is all the brutality of those who want to overwhelm, bring to their knees, deprive of identity, independence, life someone else because someone had the daring to take his place.

Useful are the words of Susan Brownmiller who in 1975 in a text defines rape: “a conscious process of intimidation with which all men keep all women in a state of fear”. In other words, according to Brownmiller, rapists do not rape because they want to have sex, they rape because they want to exert a psychological (and also physical) power on the woman, in fact in the Craven movie there is no desire in it. The eye of the spectator makes it difficult to look, to keep his gaze, to accept the image: there is all the brutality of those who want to overwhelm, bring to their knees, deprive of identity, independence, life someone else because someone had the daring to take his place.

Rape: starting from the sexual zone to triumph over the social territory

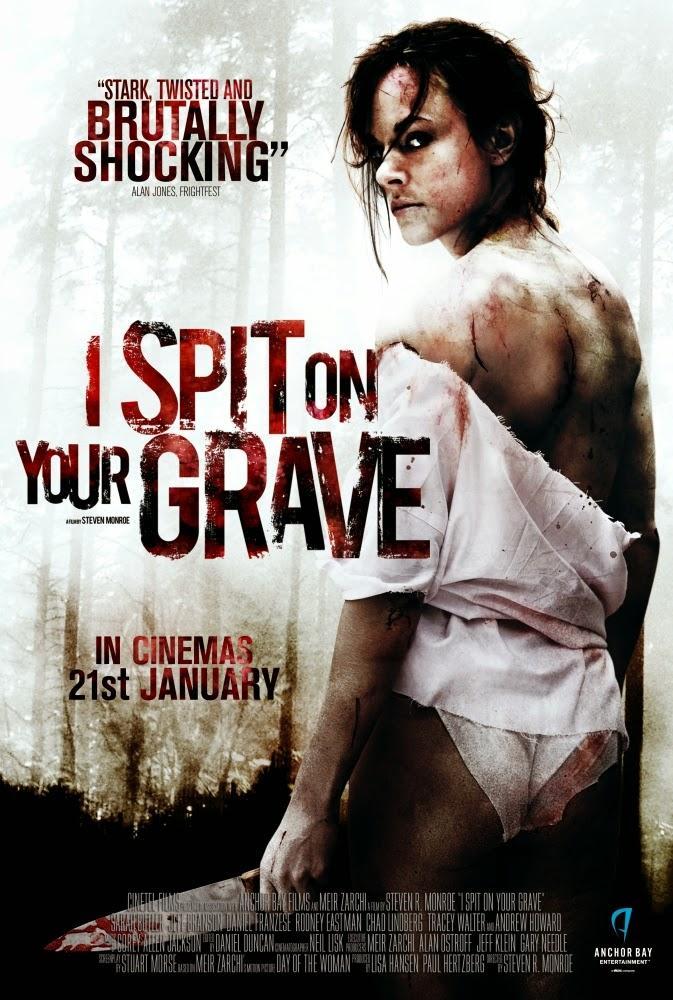

Rape represents a masculinity in crisis, in need of confirmation, the negotiation of masculinity takes place through rape. Thinking of a film like “I spit On Your Grave”, both in the version of 1978 (Meir Zarchi) and the one of 2010, it continues to be evident that rape is not an eroticized scene, light, staging do not aim at this, there are no body close-ups.

The pack humiliates, rapes Jennifer who comes from town to find refuge in the countryside, so she can work on the novel

She’s arrived there by herself, she’s the daughter of the sexual and feminist revolution. Represented as a privileged town in a vicious and uninhibited New York, it fascinates and “scares” young people, as Johnny, Stanley, Andy and Matthew, whom she meets in a gas station. For them she is promiscuous and provocative, just because she comes from the city, so she must be ready for it: for this reason, they rape her. In ’78, at the centre of the debate, there is still the guilt of the victim, which is clearly in the hands of the rapists: ignorant and violent men trapped in a stagnant economic-social condition. Rape takes the form for the group as a kind of male sport, something that has to do with the hierarchical order, which becomes social order, and, only at the end, with having sex.

She’s arrived there by herself, she’s the daughter of the sexual and feminist revolution. Represented as a privileged town in a vicious and uninhibited New York, it fascinates and “scares” young people, as Johnny, Stanley, Andy and Matthew, whom she meets in a gas station. For them she is promiscuous and provocative, just because she comes from the city, so she must be ready for it: for this reason, they rape her. In ’78, at the centre of the debate, there is still the guilt of the victim, which is clearly in the hands of the rapists: ignorant and violent men trapped in a stagnant economic-social condition. Rape takes the form for the group as a kind of male sport, something that has to do with the hierarchical order, which becomes social order, and, only at the end, with having sex.

In the 2010 remake the action engine is the loss of masculinity; in fact, the whole thing is unleashed by Johnny who cannot bear the rejection of Jennifer – especially in front of others – and so meditates revenge. “That miserable little bitch came here for one reason, showing off and provoking everyone she meets. They are all like that, city bitches who make you believe and then they don’t fit”. This version gives a different picture. The rape turns into a punitive act, in a “desperate” gesture to take back his place: Johnny (re)confirms its power – towards the woman, among the ranks of their group and within the community -, his membership in the phallocratic society, demonstrating his own social and patriarchal control in order to restore it.

In the 2010 remake the action engine is the loss of masculinity; in fact, the whole thing is unleashed by Johnny who cannot bear the rejection of Jennifer – especially in front of others – and so meditates revenge. “That miserable little bitch came here for one reason, showing off and provoking everyone she meets. They are all like that, city bitches who make you believe and then they don’t fit”. This version gives a different picture. The rape turns into a punitive act, in a “desperate” gesture to take back his place: Johnny (re)confirms its power – towards the woman, among the ranks of their group and within the community -, his membership in the phallocratic society, demonstrating his own social and patriarchal control in order to restore it.

The point of view is male: one of the rapists has a video camera that films every violence, from the body of Jennifer to the violence

The imposed sexual act is thus spectacularized and the viewer becomes a peeping tom who spies, almost an accomplice to this endless tragedy. Language becomes a cruel weapon with which the victim is ridiculed, made like an animal: “I want to see your teeth, you are a filly on display”, “Get on your knees and whine”, “You must be tamed filly”. When Jennifer takes her revenge, she repeats very precisely all the tortures she suffered.

She humiliates the rapists: they are horses for mounts, and evict them since they’re not Men and so they don’t need the member. She then deprives them of the eyes, those same that have looked at her, that wanted and undressed her. She dips them in an abrasive liquid that scraps them as they did to her.

The “culture of rape” and the famous scene of La Ciociara with Sophia Loren

Rape is not only one of the most despicable, abject, disgusting actions but it is the son of an attitude, a way of thinking; suffice it to remember that just on rape are based the “media” invectives that men of any political group, of any social class often use to ridicule, offend and silence women. There is a “rape culture” that indicates different forms of violence, not just physical violence.

The act is a political problem and it is not a case that often it was a “technique” with which in war the winner reaffirmed his supremacy by annihilating the women of the won population

The terrible scene of “La Ciociara”, by Vittorio De Sica, in which Sophia Loren witnesses the violence on her daughter and happens to her too. A scene that hurts the eyes of the viewer and incredibly seems to represent something different than the films previously mentioned; explodes the terrified and crying face of these two women who suffer what they suffer because they represent the defeated nation. Screams, wide eyes, open mouths that can’t make sounds, bodies that try to escape, to protect themselves to the last moment: this is the account of an action with a value that goes beyond the violence itself – which is already of unlimited gravity – touching even deeper chasms that affect society, often unable to translate not only into words but also into facts the concept of respect, equality, dignity. Often moving images manage to reach and move what a listened story to is not able to do and therefore can serve to understand that much can and must be done for the condition of the woman.

The terrible scene of “La Ciociara”, by Vittorio De Sica, in which Sophia Loren witnesses the violence on her daughter and happens to her too. A scene that hurts the eyes of the viewer and incredibly seems to represent something different than the films previously mentioned; explodes the terrified and crying face of these two women who suffer what they suffer because they represent the defeated nation. Screams, wide eyes, open mouths that can’t make sounds, bodies that try to escape, to protect themselves to the last moment: this is the account of an action with a value that goes beyond the violence itself – which is already of unlimited gravity – touching even deeper chasms that affect society, often unable to translate not only into words but also into facts the concept of respect, equality, dignity. Often moving images manage to reach and move what a listened story to is not able to do and therefore can serve to understand that much can and must be done for the condition of the woman.

This is the english section of

This is the english section of